‘King and Conqueror’: How much truth-stretching is acceptable?

Harold of Wessex in the bath

Welcome back to another Medieval Monday blog. After several posts dissecting the lead up to the Great Rebellion of 1173-4, today I’m switching focus to another seismic moment in English history: the Norman Conquest of England, as reimagined in the TV programme King & Conqueror.

The show has stirred plenty of excitement, and equally as much critique, about just how faithful a retelling it is. Because of that, I was loathe to watch it, but now I have, and here’s my view.

In short: yes, it draws on real events, but takes dramatic licence freely. The question is: when storytelling trumps scholarship, how much is too much?

What King and Conqueror Gets Right

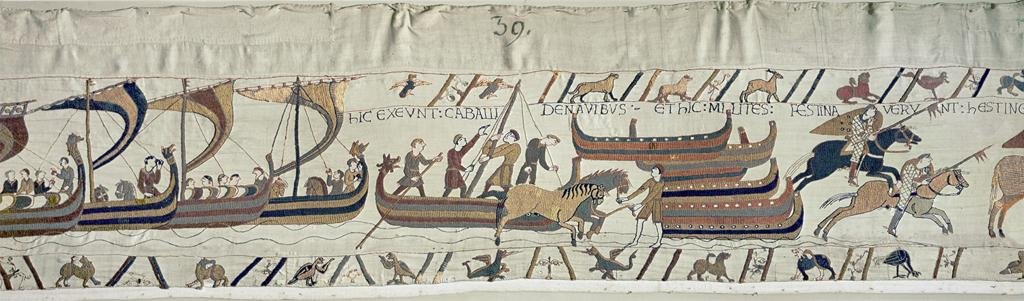

The Norman Invasion depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry

The broad arc is historically grounded: the 1066 invasion, the fatal clash at the Battle of Hastings, and the ascension of William the Conqueror as King — all of that happened, and the series uses that backbone.

Some of the lesser-known but plausible elements remain intact: for example, the appearance of Halley's Comet in 1066, a celestial omen that people at the time might well have interpreted as portentous. The show uses that touch to deepen sense of destiny and doom.

The drama does succeed at bringing the human cost, tension, and political stakes to life: the mix of ambition, betrayal and shifting allegiances reflects the general chaos and uncertainty of eleventh-century England. For many viewers, that emotional truth resonates even if details shift.

In short: at a high level, King & Conqueror delivers a sweeping, dramatic re-imagining of a world-changing event, and that alone can spark interest in a period too often overshadowed by later eras.

Where the Drama Breaks from History

William the Bastard in the bath

But, and it’s a big “but”, the series diverges from what historians believe may actually have happened.

The often-shown early meeting between William and Harold Godwinson (even a bath scene together!) is almost certainly fictional. In the show they meet in 1043 at the coronation of Edward the Confessor, but most historians date their first real rendezvous to around 1065 in Normandy.

Several major plot points: murder, sudden power-plays, dramatic deaths (some at the hands of characters in the show) appear to be invented. For instance, the show depicts Edward violently disposing of his mother; historians assert this never happened; she was stripped of power, exiled, but not murdered.

Some relationships are oversimplified or changed for clarity or or dramatic effect. The show collapses complicated family trees, renames characters, and adjusts alliances, at the expense of nuance and historical accuracy.

Costume, language, and cultural representation, not to mention casting choices, have been questioned by experts. The show leans on modern sensibilities and dramatic shorthand, which can misrepresent how 11th-century England really looked, sounded and felt.

All of this raises an inevitable tension: a drama that wants to feel epic and accessible often ends up bending or rewriting history. But was that really necessary?

The Purpose of Historical Drama: Entertainment vs Education

In LADY OF LINCOLN, I have tried my absolute best to stay accurate to the events of Nicola’s life, the city of Lincoln, her demesne, and English, Norman, and world events. It’s the unknown bits of history, and the motivations behind the discoveries, in my view, that create compelling historical fiction.

Personally, I think there’s enough potential conflict in history without having to change it. When I discovered certain facts, for example, about Nicola’s uncle, Ralph, I looked deeper, confirmed my facts, and realised I’d found a potential gem of family conflict that was of previously unrecognised national importance. It was delving deep that I found this hidden gems; I didn’t need to change what is known, I only needed to think about motivations and fill in the gaps.

But with King and Conqueror, I find myself asking: is historical accuracy the only yardstick by which to judge? Or can we accept a “truth-plus-fiction” approach, so long as it brings the era to life, generates interest, and perhaps drives new viewers to dig deeper?

For many, the answer will differ depending on what you want from it.

If you’re a history purist, committed to medieval detail and academic truth, the liberties taken may feel like betrayal — a distortion of a moment with real human consequences.

But if you approach it as a gateway: a way to feel the drama, the stakes, the human emotions, and then explore the historical record on your own, there’s value in that.

For me, the key is transparency: recognising that what we see on screen is as much myth and interpretation as it is history.

But if it brings more people into the world of historical fiction and medieval history, then all to the good!

My verdict on King and Conqueror: enjoy, but read the footnotes!

Much as I myself have tried to keep to the known facts (and fill in the spaces), I believe there is room in modern storytelling for works like King & Conqueror. As long as we watch with eyes open, aware of its dramatic licence, it can be a valuable and even inspirational retelling of a world-changing moment.

But I’d urge viewers who fall under its spell to treat it as the beginning, not the end, of learning about 1066. Read up on the real events, explore contemporary sources and materials like the Bayeux Tapestry, and try to separate fact from fiction.