WELCOME TO RACHEL’S BLOG

Scroll down to see the most recent posts, or use the search bar to find previous blogs, news, and other updates

All Hallows’ Eve: The Vigil of the Departed

When twilight falls on 31 October, the Christian calendar and the old pagan year meet.

The Eve of All Hallows—from Old English hālga ǣfen (“holy evening”)—was the vigil before the Feast of All Saints.

Yet in spirit it still carried the echo of Samhain, the Celtic festival of endings and beginnings.

In pagan belief, this was the night when the barrier between worlds dissolved: the dead might revisit hearth and home, and the living could glimpse the Otherworld. Fires blazed, food was laid out for ancestors, and villagers disguised themselves to ward off or impersonate wandering spirits.

Lanterns and Mischief: From Samhain Fires to Punkie Night

In the ancient Celtic world, Samhain marked the moment when the year tipped into darkness. Bonfires blazed on hilltops, not as mere celebration but as protection—flames to cleanse, to guard livestock, and to guide wandering souls.

When Christianity spread, the bonfire’s symbolism endured. The Church kindled its own light—candles of vigil—burning in churchyards and windows on the eve of All Hallows’ Day, turning pagan flame into prayer.

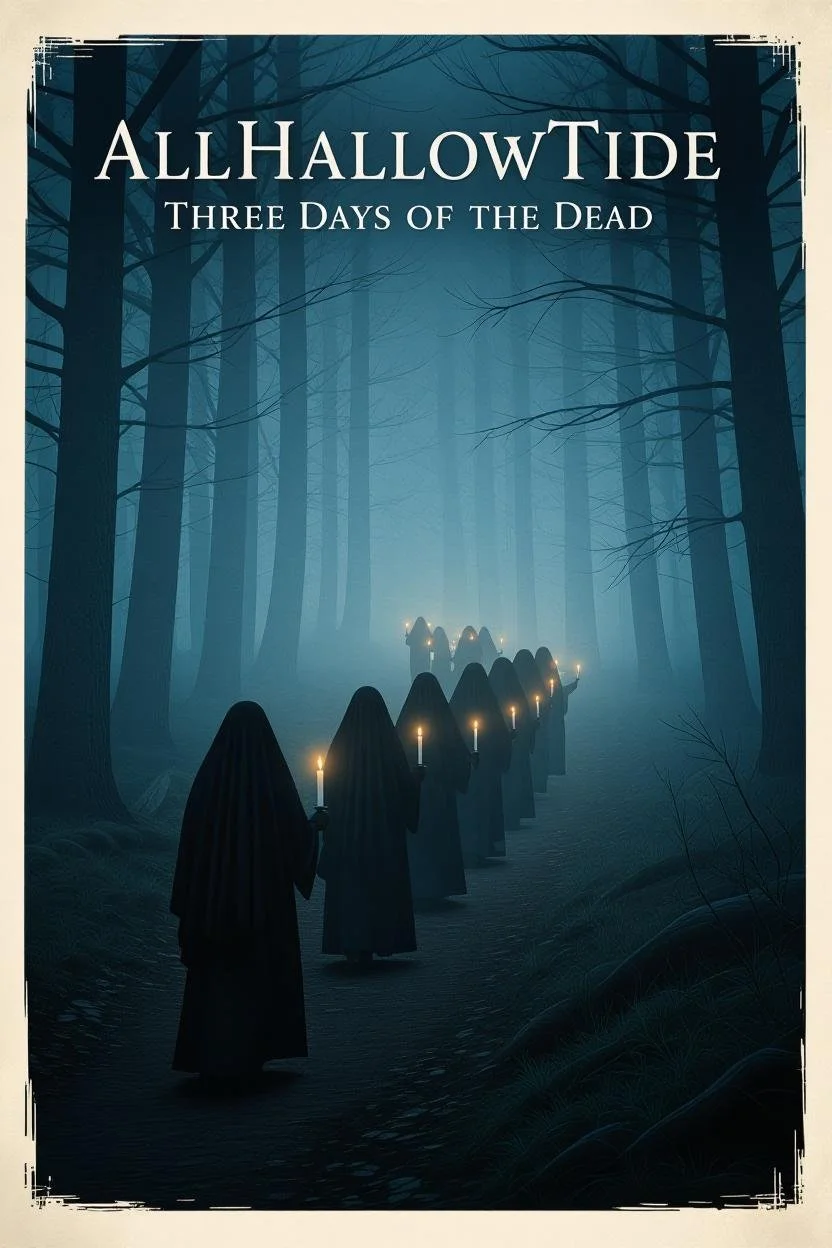

What Is Allhallowtide? The Three Days of the Dead…

As the last leaves fall and nights lengthen, the medieval calendar turns toward Allhallowtide—three days devoted to saints, souls, and the turning of the year.

The word comes from hallow (Old English hālga, “holy person”) and tīd (“time” or “season”).

For Christians of the Middle Ages, it was a sacred hinge between worlds: a time to honour the saints in heaven, pray for souls in Purgatory, and remember the dead on earth.

But these days did not arise from nowhere. Long before church bells rang, the Celts gathered at Samhain—literally “summer’s end.” The festival marked the boundary between the light and dark halves of the year, when harvest was over and the veil between living and dead grew thin.