Medieval New Year's Eve: When Chaos Was the Point

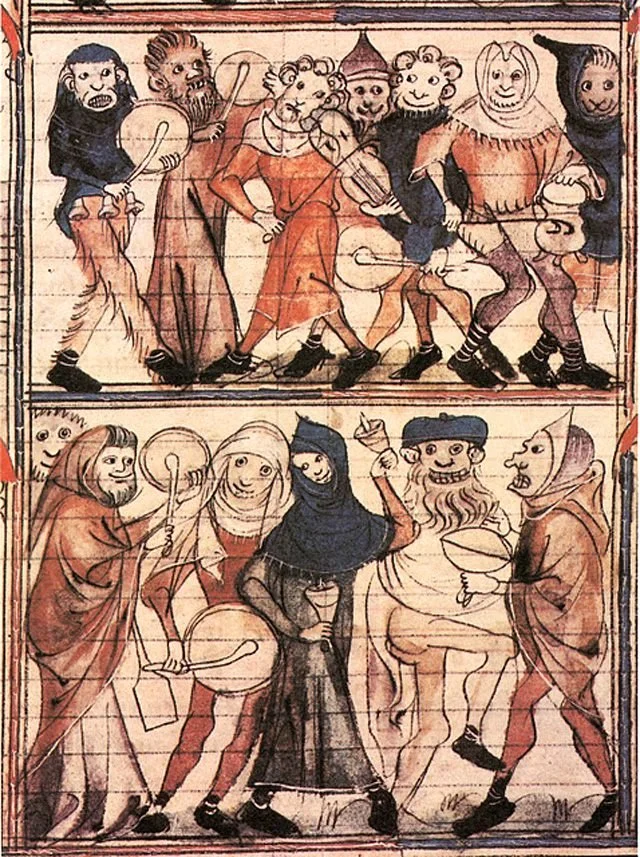

The Medieval Feast of Fools

Forget champagne at midnight and awkward renditions of "Auld Lang Syne." Medieval New Year's was an entirely different beast, and honestly? It sounds way more fun.

Across Europe, the turning of the year wasn't just a date on the calendar. It was a full-blown excuse to flip everyday life on its head, stuff your face with roasted meat, and generally behave in ways that would make your local priest extremely nervous.

The Feast of Fools: Your Annually Scheduled Revolution

The Festival of Fools

Picture this: It's January 1st in a medieval town. The lowly church clerks and regular townsfolk have just elected a "Pope of Fools." They're parading through the streets in ridiculous costumes, possibly drunk, definitely making a mockery of sacred rituals. There's dancing. There's dice rolling during church services. Someone's definitely cross-dressing. It's absolute pandemonium.

Welcome to the Festum Fatuorum—the Feast of Fools.

What started as cheeky bits of playacting during Christmas church services eventually spiraled into something gloriously unhinged. By the later Middle Ages, you had masked dances, muddy street parades, and the kind of irreverent chaos that eventually made church authorities say "okay, that's ENOUGH" and ban the whole thing in the 15th century. (Though, naturally, people kept doing versions of it anyway because people have always been delightfully stubborn about their fun.)

Think of it as medieval Mardi Gras meets The Office Christmas party, but with more livestock in the streets.

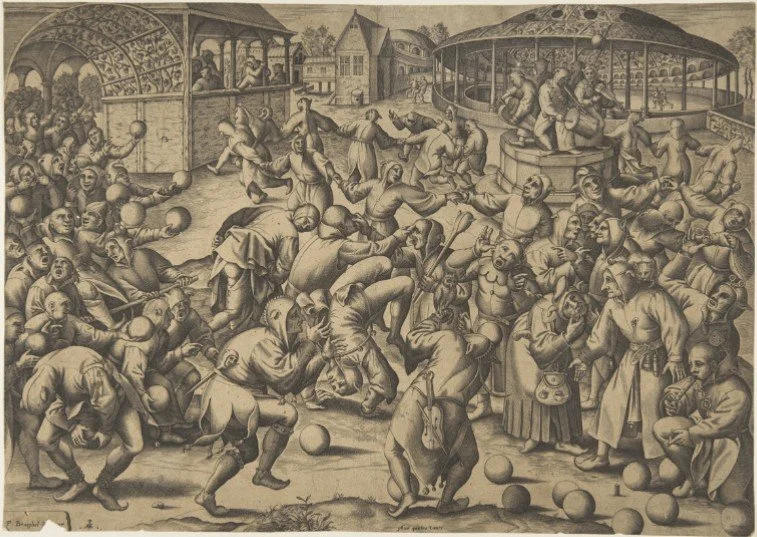

Feasting Like the World Might End (Because It Might)

A medieval feast

Beyond the sanctioned chaos, winter feasting was serious business. Those long, dark December and January nights weren't going to get through themselves. Communities gathered around tables groaning with roasted meats, spiced breads, and the kind of hearty stews that stick to your ribs and make you forget that spring is still months away.

Yes, the Church side-eyed some of these festivities—especially the ones that felt a bit too much like those old Roman Saturnalia parties. But people found their loopholes. Wassail cups made the rounds. Yule logs burned. And somehow, religious solemnity and full-throated revelry managed to coexist in a beautiful, slightly drunk harmony.

Why All the Topsy-Turvy?

There's something deeply human about wanting to flip the script when the world feels darkest. Those winter role reversals—peasants playing bishops, servants ordering nobles around for a day—likely echo ancient midwinter traditions where the normal order took a holiday.

The Romans had their Saturnalia. Medieval folks had the Feast of Fools. Both said: "For just a moment, let's pretend none of the usual rules apply."

And even though the Church kept moving the "official" New Year around (March 25! No, December 25! Actually, maybe January 1?), regular people kept marking the turn of the year with community, excess, and a healthy dose of sanctioned foolishness.

What They Gave Us

We may not parade through town in muddy rags or elect fake popes anymore, but the spirit lives on. New Year's Eve countdowns, satirical year-end specials, the absurd optimism of resolutions we'll abandon by February—it's all part of that same medieval impulse.

The Middle Ages understood something we sometimes forget: the end of one year and the start of another deserves more than champagne and a kiss at midnight. It deserves laughter with friends, a table full of food, and maybe—just maybe—a brief moment where everything ordinary gets turned delightfully upside down.

So this New Year's Eve, channel your inner medieval reveller. Feast. Be ridiculous. Let chaos reign (within reason). After all, you're carrying on a tradition that's lasted centuries.