Eleanor of Vermandois

The Last Countess and Her Scandalous Family

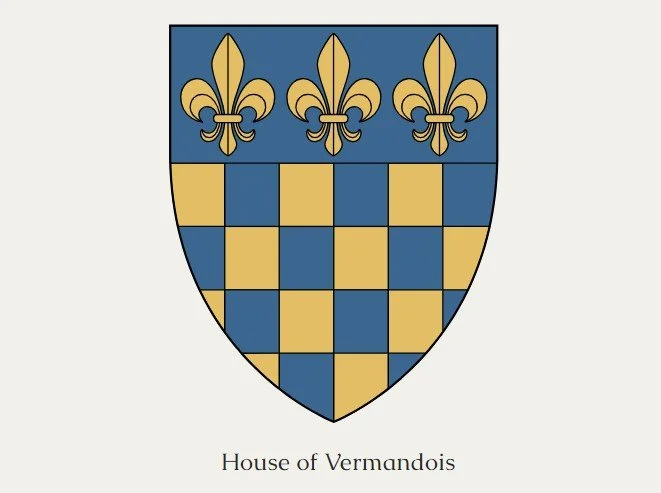

Vermandois Coat of Arms

In the shadowed corridors of twelfth-century French history stands a woman whose story has been largely forgotten—Eleanor of Vermandois (c. 1148–1213). Born into one of medieval Europe's most controversial families, Eleanor's life was marked by political intrigue, personal tragedy, and remarkable resilience as she navigated a world where powerful men controlled women's destinies.

If you're planning to read my popular, and currently free, historical novella Eleanor's Revenge, the first section of this post is spoiler-free, introducing Eleanor and her family background. Further down, after a clear spoiler warning, I delve into the full dramatic arc of her life.

A Scandalous Beginning

Eleanor's very existence was rooted in scandal. Her parents' marriage in 1142 triggered one of the most notorious affairs of the medieval period. Her father, Raoul I, Count of Vermandois, was the powerful seneschal of France and cousin to King Louis VII. Her mother, Petronilla of Aquitaine, was the younger sister of the legendary Eleanor of Aquitaine, who would become Queen of both France and England.

Their love story began at the French court around 1141, when Petronilla met the much older, married Raoul. With her sister's encouragement and the king's approval, Raoul secured an annulment from his first wife, Eleanor of Blois, on dubious grounds of consanguinity. Three compliant bishops—one of whom was Raoul's own brother—officiated at Raoul and Petronilla's wedding in early 1142.

An image of Eleanor’s Father, Count Raoul I, taken from his seal

But the scandal had only just begun. Pope Innocent II refused to recognize the annulment, declaring the marriage illegitimate and excommunicating the couple, along with the three bishops who had sanctioned the union. Even King Louis VII faced excommunication for supporting the match. The political fallout was devastating—Theobald of Champagne, brother of Raoul's repudiated wife, went to war with France. The conflict lasted from 1142 to 1144 and culminated in Louis VII's infamous burning of Vitry-le-François, where over a thousand people perished when they took refuge in a church that caught fire.

The excommunication was eventually lifted in 1148 at the Council of Reims, but Petronilla's reputation never recovered. She died sometime between 1148 and 1152, though her exact fate remains unknown. Raoul quickly remarried to Laurette of Flanders and died later that same year, in October 1152, at the Abbey of Saint-Arnoul at Crépy-en-Valois.

The Orphaned Heiress

When her father died in 1152, Eleanor was only about four years old. She and her siblings—Elisabeth (born c. 1143) and Raoul II (born c. 1145)—became wards of King Louis VII and were brought to Paris to be raised at the royal court. The children's mother had already disappeared from history, likely dead or banished to a convent for the scandal she had caused.

As the youngest and bearing the tainted name of her notorious aunt Eleanor of Aquitaine, young Eleanor probably faced contempt and isolation at court. Medieval chroniclers noted the cruel whispers about her family's alleged descent from Mélusine, the legendary serpent-woman who cursed her descendants to greatness shadowed by tragedy. The Aquitainian bloodline was viewed with suspicion—powerful, beautiful, but dangerous.

Last in line to inherit Vermandois, young Eleanor was not expected to rule. Yet fate had other plans for this forgotten daughter of scandal.

⚠️ SPOILERS AHEAD ⚠️

*If you plan to read my novella about Eleanor, Eleanor's Revenge, stop here! The following sections reveal major plot points and the full arc of Eleanor's dramatic life story.*

A Sister's Tragedy

Eleanor's elder sister Elisabeth's story epitomizes the constraints and cruelties faced by medieval noblewomen. In 1159, sixteen-year-old Elisabeth married Philip of Alsace, Count of Flanders, in a strategic alliance. The following year, their brother Raoul II married Philip's sister Margaret, further cementing the family ties.

When Raoul II died of leprosy in 1167 without children, Elisabeth inherited the County of Vermandois, ruling it jointly with her husband Philip. This pushed Flemish authority further south than ever before, threatening the balance of power in northern France. But the marriage remained childless, and by 1175, after more than fifteen years together, Philip—a cruel man—was most likely disrespectful towards his barren wife.

Then came the scandal that would destroy Elisabeth. In 1175, Philip discovered that his wife was having an affair with Gautier (Walter) de Fontaines, a knight described by chronicler Roger of Hoveden as "sprung of a noble family, and conspicuous before all his compeers in feats of arms." Philip's vengeance was brutal and public. He had Gautier stripped of his knightly honors, with his sword belt cut to pieces and his gilded spurs hacked off. The knight was then dragged through the streets of Bruges behind a horse and finally hung upside down over a sewer pit, where he suffocated to death over several agonizing days.

Elisabeth was imprisoned for life, first in Bruges and later in a convent near Arras. Philip retained control of Vermandois through her name, refusing to release the lands even after her death. She died childless, disgraced, and alone—a cautionary tale of what befell women who dared defy their husbands' authority.

Eleanor's Marriages and Power

With both her siblings dead, Eleanor became the last of the Vermandois line and found herself at the centre of a territorial struggle. Her first significant marriage was to William IV, Count of Nevers, around 1164, when she was only about sixteen. William was twice her age but the marriage seemed to go well, even if it was childless.

Tragically, William died in 1168 during a crusade to the Holy Land. According to William of Tyre, he was buried in Bethlehem at the Church of the Nativity itself—a man who had gone on pilgrimage after arguing with his local monastery.

Around 1170, Eleanor married Matthew of Alsace, Count of Boulogne and brother of the Philip of Flanders who would later imprison her sister. Matthew was notorious for having abducted Marie of Boulogne from a nunnery and forcing her to marry him for her inheritance. Historians believe this match was part of Philip of Flanders's deliberate policy to control Vermandois through family alliances. Matthew died in 1173 from a crossbow wound sustained during the Great Rebellion against Henry II of England (I cover this event in Lady of Lincoln).

Eleanor's final marriage was to Matthew (Mahieu) of Beaumont-sur-Oise, the king's Grand Chamberlain, sometime around 1175. Though of lesser lineage than her previous husbands, this marriage gave her access to royal favour. Later in their marriage, they appear to have lived separately—he at court in Paris, she increasingly in Vermandois—and had no children. Or they may simply have divorced around 1192. He died around 1208/9.

The Fight for Vermandois

After Elisabeth's death in 1183, Eleanor emerged as the rightful heir to Vermandois. But Philip of Flanders refused to surrender the territory, triggering a major conflict with the young King Philippe II of France (Philip Augustus), who had his own designs on the strategically important region.

The struggle reached its climax at the Treaty of Boves in July 1185. King Philippe II's disciplined royal army, strengthened by bishops and counts who had grown wary of Flemish overreach, forced Philip of Flanders to negotiate. The treaty was a partial victory for Eleanor: she received Valois, while Philip of Flanders retained Saint-Quentin. King Philippe received Artois, the dowry of his wife Isabelle, who was Philip of Flanders's niece.

Though Eleanor had hoped to reclaim all of Vermandois, she had at least secured Valois and established her right to rule in her own name. When Philip of Flanders died on crusade in 1191 at the Siege of Acre, his sister Margaret inherited Flanders and eventually relinquished Saint-Quentin, finally reuniting the Vermandois territories under Eleanor's rule.

A Woman Ruler

From around 1185 until her death in 1213, Eleanor ruled Valois (and eventually all of Vermandois) in her own right—a rare achievement for a medieval woman. She issued charters in her own name, styled as *Eleanora Comitissa Sancti Quentini et Valesiae* (Eleanor, Countess of Saint-Quentin and Valois). Her personal seal displayed her authority independent of any husband.

Eleanor proved to be an effective and just ruler. She dispensed justice fairly, collected taxes efficiently, and restored order to territories that had been ravaged by decades of warfare. Contemporary accounts describe her as "witty yet pious"—intelligent, cultured, and deeply religious. She was an active patron of the Church, supporting over twenty religious houses. She founded the Fontevraudine priory of Longpré and the Cistercian nunnery of Parc-aux-Dames near Auger-Saint-Vincent, setting a precedent for aristocratic women's independent religious benefaction.

Her love of poetry and literature was well-known. She encouraged the troubadour Renaud and supported his work on the *Roman de Sainte-Geneviève*. In 1189, she donated property to Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, documented in surviving charters.

The Curse of Childlessness

Despite four marriages, Eleanor left no surviving heirs. Some sources allude to a daughter who died young, possibly from her marriage to Matthew of Boulogne, but this remains uncertain. Modern historian Édouard de Saint-Phalle notes cautiously: "Eleanor left no surviving issue, though some sources allude to a daughter who died young."

The persistent childlessness that plagued both Eleanor and her sister Elisabeth gave credence to the whispered tales about the curse of Mélusine. The legend held that the serpent-woman's descendants were doomed to greatness shadowed by loss—power tempered by barren wombs and broken hearts.

Legacy and Death

Eleanor died on June 19 or 21, 1213, at approximately sixty-four years of age, having ruled for nearly thirty years. She was buried at the Abbey of Longpont, the traditional necropolis of the Vermandois family, beside her brother Raoul II. Her epitaph read simply: *Eleanora Comitissa de Vermandis*—Eleanor, Countess of Vermandois.

With no heirs, Vermandois passed to the French crown as King Philippe II had long intended, becoming part of the expanding Capetian royal domain. Her death marked the end of the Vermandois dynasty, a line that had been one of the most powerful noble houses in northern France.

A Forgotten Woman of Power

The Seal of Eleanor of Vermandois

Eleanor of Vermandois's story reveals the complex reality of medieval noblewomen's lives. Born into scandal, orphaned young, and shaped by the tragedies that befell her family, she nevertheless carved out a space of autonomous power in a world designed to deny it to women.

Her career marks the transition from feudal independence to Capetian centralisation, but it also stands as a rare example of sustained female governance in twelfth-century France. In an age that offered women little freedom, Eleanor of Vermandois survived through intellect, political acumen, and sheer determination.

Yet for all her achievements, history has largely forgotten her. Overshadowed by her more famous aunt Eleanor of Aquitaine and eclipsed by the scandals that marked her family, the last Countess of Vermandois deserves recognition as a remarkable woman who wielded power despite overwhelming odds.

Her story reminds us that behind every great medieval king stood not just queens, but countesses, heiresses, and women rulers whose stories have been lost to time. Eleanor of Vermandois was one such woman—the last of her line, shaped by tragedy, but determined to rule with justice and strength.

My historical novella Eleanor's Revenge brings this forgotten countess's story vividly to life, weaving historical fact with emotional depth to reveal a woman whose resilience and determination shine across the centuries.

---

*Note: This blog post draws on historical sources including contemporary chroniclers like Roger of Hoveden, Gislebert of Mons, and William of Tyre, as well as modern scholarship by historians including Constance Hoffman Berman, Charlotte Pickard, and Édouard de Saint-Phalle.