Medieval Advent

The Season That Modern Advent Barely Resembles Its Origins

Everyone is talking about what they have in their advent calendars: chocolates, toys, even Star Wars characters! Advent also brings to mind glittering candles on wreaths, festive jumpers, Christmas markets, mulled wine, and the countdown to Christmas morning.

I haven’t met a single person (other than fellow medieval fiction authors) who have any idea that for medieval people, Advent was not a season of indulgence or celebration. It was a period of fasting, penance, self-examination, and preparation for the Second Coming rather than Santa’s sleigh.

The earliest evidence for Advent appears in the 4th century, particularly in Gaul and Spain, where Christians observed a multi-week fast before Epiphany rather than Christmas. This early “Nativity Fast” resembled Lent: No meat, no dairy, no rich foods, no marital relations (yes, this was explicitly addressed!). By the 6th century, Rome formalised a four-week liturgical season leading up to Christmas. But unlike today’s “anticipatory joy,” medieval Advent preached repentance, vigilance, and apocalyptic expectation.

The focus wasn’t solely on celebrating Christ’s birth. Advent was designed to prepare the soul for Christ’s return in judgement. Medieval sermons emphasised humility, fear of sin, confession, charitable giving, and moral renewal. The message was clear: Christmas might be coming, but so was Judgement Day!

If modern Advent is “countdown to the festivities,” medieval Advent was “brace yourself and prepare your soul.”

Fasting and Dietary Restrictions

Medieval Advent Food was Fasting Food

Advent was a penitential fast, with regional variations. In many places this meant: no meat, no cheese or eggs, no alcohol (or heavily restricted alcohol), meals reduced to once a day or two light meals, no frivolous feasting until Christmas Eve, with the richness of December farming and hunting yields - pork, dairy, winter ale - deliberately withheld.

Marriage was forbidden during Advent. So were major feasts, dances, and revelry. It was a quiet season focused on sobriety and restraint.

But although the season was austere, it was not joyless. Medieval communities developed a rich set of traditions, but they were deeply rooted in devotion, not decoration.

The Rorate Mass

One of the most beautiful medieval Advent traditions, still practiced in some places today. They were held before dawn, dedicated to Virgin Mary, and celebrated entirely by candlelight, symbolising the coming light of Christ into the darkness of the world. Villagers trudging through frozen fields to a dark church lit only by beeswax candles: this is Advent as the Middle Ages knew it.

Monks and nuns observed the strictest Advent discipline, with silence at meals, additional night vigils, greater almsgiving, the reading from prophetic books like Isaiah, and elaborate choral pieces for the season

For them, Advent was a journey inward, and a cleansing of the soul.

What Did Medieval People Eat in Advent?

With meat and dairy restricted, the medieval Advent table required creativity. Common Advent foods included: Pottages and vegetable stews -often thickened with barley, oats, or legumes; root vegetables and winter greens: Onions, leeks, cabbage, parsnips — all staples; fish: dried, smoked, pickled, or fresh if one lived near water. Eel was particularly popular.. Without dairy, they used, almond milk: a key dairy substitute in wealthy households. They still had bread, of course: Black rye bread for the poor; wheaten loaves for the wealthy.

Interestingly, Christmas Eve, which was the final day of fasting, often saw families holding out until the night Mass before the real feasting began.

Community Rituals and Charity

Advent was also a time when medieval society emphasised almsgiving and hospitality. The poor received bread and ale, fish, warm clothing, and charitable distributions from monasteries or wealthy manors.

Performances and Preaching

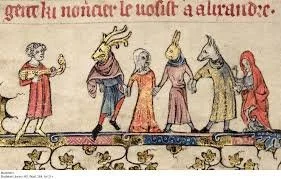

A Medieval Morality Play

Though formal revelry was discouraged, towns hosted moral plays, scriptural readings, and travelling preachers urging repentance (you can just imagine…)

So When Did Advent Become… Fun … or perhaps even Commercialised?

The turning point came gradually with 19th-century German traditions introducing Advent wreaths and calendars, commercial printing turning calendars into children’s treats by the early 20th century, Victorian Christmas culture softening Advent’s tone from penitential to anticipatory. And finally, post-WWII consumerism finally rewrote Advent, incorporating it into the festive season.

Today, Advent is, as we know not just cosy, decorative, but celebratory, and commercialised. By contrast in the Middle Ages, advent was quiet, serious, introspective, and spiritually disciplined. Perhaps we lost something along the way…