Wu Zetian: The Woman Who Ruled an Empire

Forgotten Women of History

Wu Zetian, Empress of China

When we think of medieval power, the mind rarely leaps to a woman occupying the highest throne in one of the world’s greatest empires. Yet in 7th-century China, one woman did precisely that. Wu Zetian (624–705 CE) rose from low-ranking concubine to become China’s only female emperor; not merely empress consort, nor regent, but sovereign ruler in her own right.

In a world shaped by Confucian ideals that explicitly declared women inferior and unfit for leadership, her ascent was nothing short of astonishing.

And like many powerful women in history, Wu Zetian has been remembered through a haze of scandal, propaganda, and deliberate distortion. It’s time to peel back the layers and re-examine the woman behind the legend.

From Concubine to Emperor: A Rise Unlike Any Other

Wu Zetian entered the palace of Emperor Taizong as a teenage concubine; one among hundreds, hardly expected to influence politics. After Taizong’s death she should, by custom, have been sent to a Buddhist convent. Instead, she returned to the palace of his successor, Emperor Gaozong, beginning her ascent through skill, cunning, and what later historians would call “unwomanly ambition.”

Smooth Operator

But ambition alone did not place her on the throne. She possessed a sharp intelligence and administrative brilliance; a talent for identifying capable officials, many of whom became her loyal supporters; and a capacity to counter, outmanoeuvre, or neutralise rival factions.

When Gaozong suffered debilitating strokes, Wu Zetian took charge of state affairs. After his death, she ruled first through her sons and eventually dispensed with that formality entirely, proclaiming her own dynasty: the Zhou, and naming herself Huangdi, the imperial title previously reserved for male rulers.

Her rule was marked by expanding the imperial examination system, allowing men of talent (not merely noble birth) to enter government; strengthening central administration; territorial expansion and increased influence abroad; support for Buddhism, which offered philosophical frameworks more favourable to female authority than Confucianism

As is so often the case under female leaders of the past, under her reign, China experienced relative stability, prosperity, and artistic flourishing.

Villain or Visionary?

If Wu Zetian had been a man, her decisive leadership would likely have earned her a place among China’s greatest emperors. Instead, traditional historiography, written by male scholars invested in Confucian gender order, branded her cruel, manipulative, lascivious, and bloodthirsty.

Wu Zetian could be ruthless. Power in the Tang court was a dangerous sport, and she did what male rulers routinely did: remove rivals, consolidate authority, and secure her dynasty’s future. But her crimes have often been magnified, while her achievements were obscured.

Modern scholarship offers a more balanced view: Wu Zetian was neither a demon nor a saint, but an effective and deeply complex ruler navigating a structure designed to exclude her.

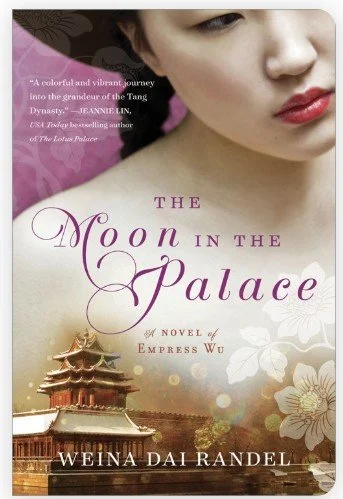

Wu Zetian in Fiction: The Moon in the Palace by Weina Dai Randel

The Moon in the Palace by Weina Dai Randel

Historical fiction has taken a renewed interest in Wu Zetian, none more beautifully than in Weina Dai Randel’s duology, beginning with The Moon in the Palace and followed by The Empress of Bright Moon.

Randel’s portrayal is intimate, lush, and deeply human. Rather than focusing solely on imperial politics — though these are richly rendered — she brings readers into the emotional and psychological world of Wu Mei (Wu Zetian’s young name), a girl navigating the perilous hierarchy of the Tang palace.

What Randel’s Duology Captures Particularly Well

The claustrophobic glamour of palace life

Silk screens, whispered alliances, night-time summons, coded etiquette — Randel excels at showing the fragile, gilded cage that shaped Wu Mei long before she became empress.

The intelligence and restraint behind her rise

Randel emphasises Wu Mei’s scholarship, curiosity, and intuitive understanding of power. Her Wu Zetian is not a scheming temptress, but a strategist forced to walk a razor’s edge.

The emotional costs of ambition

Love and loyalty become dangerous luxuries. The duology explores Wu Mei’s inner conflicts — desire vs. duty, personal happiness vs. survival — reminding readers that power never comes without sacrifice.

A challenge to the traditional femme fatale narrative

Where official histories cast Wu Zetian as a villain, Randel restores her humanity. Her protagonist is fallible, passionate, courageous, frightened, determined - in other words, real.

These novels cannot replace scholarship, nor do they claim to. But they offer an imaginative, empathetic entry point into the life of a woman too often flattened into caricature.

Wu Zetian’s story is one of resilience, intelligence, and audacity in a world stacked against her. Whether through rigorous histories or the sweeping romanticism of Weina Dai Randel’s duology, her life invites us to question the narratives we inherit, and whose voices are missing from them.

A woman rose to become emperor, and her story deserves to be told.