WELCOME TO RACHEL’S BLOG

Scroll down to see the most recent posts, or use the search bar to find previous blogs, news, and other updates

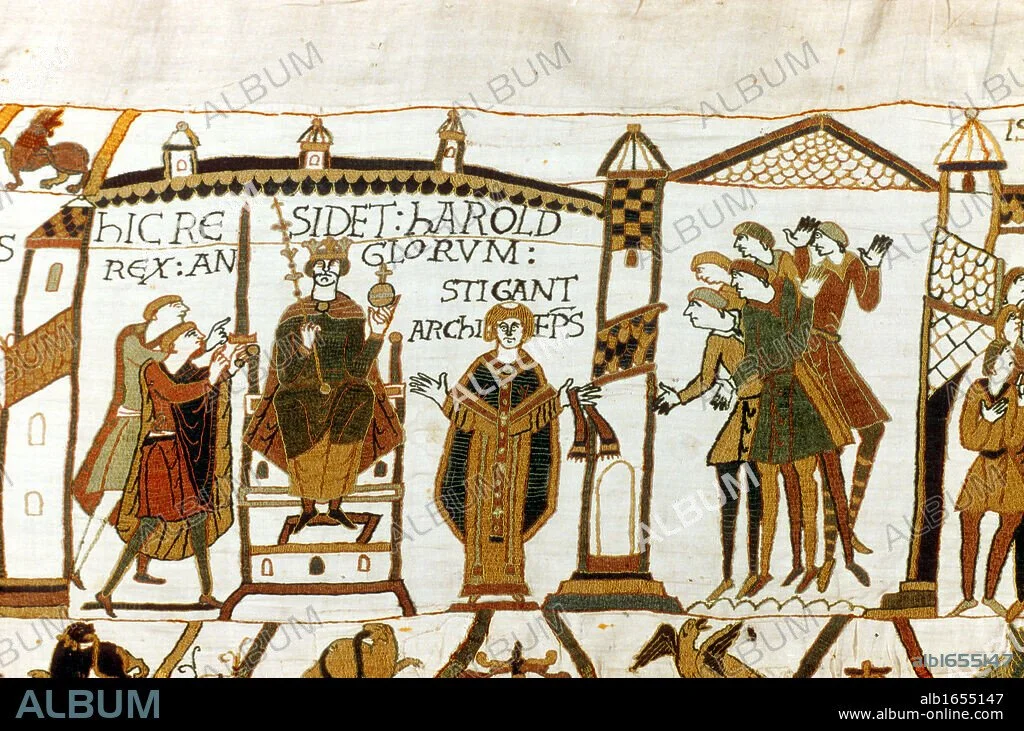

The Saxon Secret to Avoiding a Bad Ruler

What if the worst rulers in English history didn't have to happen?

Bad kings - the weak, the cruel, the catastrophically incompetent - weren't inevitable. They were the consequence of a system that handed the most powerful job in the kingdom to whoever happened to emerge from the right womb in the right order!

Primogeniture, succession by (male) birth order, gave England Edward II, whose personal failings and political incompetence ended in his deposition and probable murder. It gave England Richard II, whose erratic tyranny triggered a constitutional crisis and cost him his throne. It gave England Henry VI, whose mental collapse plunged the country into thirty years of civil war. These weren't accidents of fate. They were what happens when a system prioritises birth order over every other human quality.

But before the Normans locked this system in place, the Anglo-Saxons did something far more interesting.

The Aetheling System: Choose the Best, Not the First

Herstory Refuses to Be Forgotten!

ady of Lincoln opens in 1168, when a fourteen-year-old Nicola de la Haye stood in the barracks of Lincoln Castle, a young girl surrounded by sleeping soldiers, determined to help a boy who didn't belong. It was a small act of defiance in a world that would soon demand much larger ones.

I'm honoured to share that Lady of Lincoln has been named a semi-finalist in the 2025 Chanticleer Chaucer Awards for Early Historical Fiction.

The novel has already won awards, and this is a highly prestigious one. Chuffed as I am, it’s not really about awards and recognition that I can weave a good tale (although I’m thrilled about that!). It's about what Nicola's story represents—a woman who inherited a barony and a castle in her own right, who found herself caught between impossible loyalties when her husband joined the Great Rebellion of 1173-4, and who chose to defend what was hers.

That’s what inspired me to write about her in the first place.

Fastrada: Charlemagne’s Queen History Tried to Forget

Charlemagne is usually thought of as the iron-willed king, crowned Emperor of the Romans in 800, architect of a European empire and champion of learning and reform. What we never hear about, however, are the women who stood beside him: women whose influence shaped politics, justice, and the fragile stability of his realm.

One of the most controversial of these women was Fastrada, Charlemagne’s fourth wife and queen, a woman remembered less for what she did than for how male chroniclers chose to describe her.

A Frankish Noblewoman in a Dangerous Court

Fastrada was born into the high Frankish nobility around the mid-8th century, the daughter of Count Radulf. Her marriage to Charlemagne in 783 was not a romantic match but a strategic one, strengthening ties between powerful families within the Frankish heartlands. This was a period when Charlemagne’s empire was expanding rapidly through conquest, forced conversion, and ruthless suppression of revolt.

Queens in the Carolingian world were not crowned consorts in the later medieval sense, but they were far from ornamental. They managed households, acted as intermediaries, dispensed patronage, and, crucially, advised the king. Fastrada arrived at court at a moment when Charlemagne’s rule was under strain from internal rebellion, particularly in Saxony.

“Cruel” Queen or Convenient Scapegoat?

Our surviving sources paint Fastrada in dark colours. Einhard, Charlemagne’s biographer, describes her as harsh and cruel, claiming that her influence made the king more severe in judgement. Later chroniclers echoed this, blaming her for brutal punishments meted out against rebels and dissenters.

But this raises an uncomfortable question: Was Fastrada truly cruel, or was she blamed for decisions Charlemagne himself made?

Early medieval queens were often held responsible when kings ruled harshly. Advising firmness could easily be reframed as bloodthirstiness, especially when the adviser was a woman. Fastrada’s reputation may tell us more about medieval anxieties over female influence than about her actual character.

It is worth noting that Charlemagne’s most notorious acts of brutality, including the mass executions of Saxons, predated and outlasted Fastrada’s life. Yet only she became a symbol of excessive severity.

Feasts, Folklore & Boar: A Medieval Christmas with a Dash of Wild Hunt Magic

Christmas is coming; and if you think today’s festive spread is decadent, just imagine what a medieval English banquet looked like! Long before turkeys were discovered in America, people from monks to monarchs gathered round a banquet table groaning with pies, ale, spiced wine, and one very impressive centrepiece: the boar’s head.

Wu Zetian: The Woman Who Ruled an Empire

When we think of medieval power, the mind rarely leaps to a woman occupying the highest throne in one of the world’s greatest empires. Yet in 7th-century China, one woman did precisely that. Wu Zetian (624–705 CE) rose from low-ranking concubine to become China’s only female emperor; not merely empress consort, nor regent, but sovereign ruler in her own right.

In a world shaped by Confucian ideals that explicitly declared women inferior and unfit for leadership, her ascent was nothing short of astonishing.

And like many powerful women in history, Wu Zetian has been remembered through a haze of scandal, propaganda, and deliberate distortion. It’s time to peel back the layers and re-examine the woman behind the legend.

From Concubine to Emperor: A Rise Unlike Any Other

Wu Zetian entered the palace of Emperor Taizong as a teenage concubine; one among hundreds, hardly expected to influence politics. After Taizong’s death she should, by custom, have been sent to a Buddhist convent. Instead, she returned to the palace of his successor, Emperor Gaozong, beginning her ascent through skill, cunning, and what later historians would call “unwomanly ambition.”

Smooth Operator

But ambition alone did not place her on the throne. She possessed a sharp intelligence and administrative brilliance; a talent for identifying capable officials, many of whom became her loyal supporters; and a capacity to counter, outmanoeuvre, or neutralise rival factions.

When Gaozong suffered debilitating strokes, Wu Zetian took charge of state affairs. After his death, she ruled first through her sons and eventually dispensed with that formality entirely, proclaiming her own dynasty: the Zhou, and naming herself Huangdi, the imperial title previously reserved for male rulers.

Zenobia of Palmyra: the Queen Who Defied Rome

In the third century CE, as Rome teetered on the brink of fragmentation, a woman from the desert city of Palmyra rose to challenge the empire itself.

Her name was Zenobia — scholar, strategist, queen, and for a brief, extraordinary moment, empress of the East.