Feasts, Folklore & Boar: A Medieval Christmas with a Dash of Wild Hunt Magic

And when Nicola de la Haye goes on a Hunt

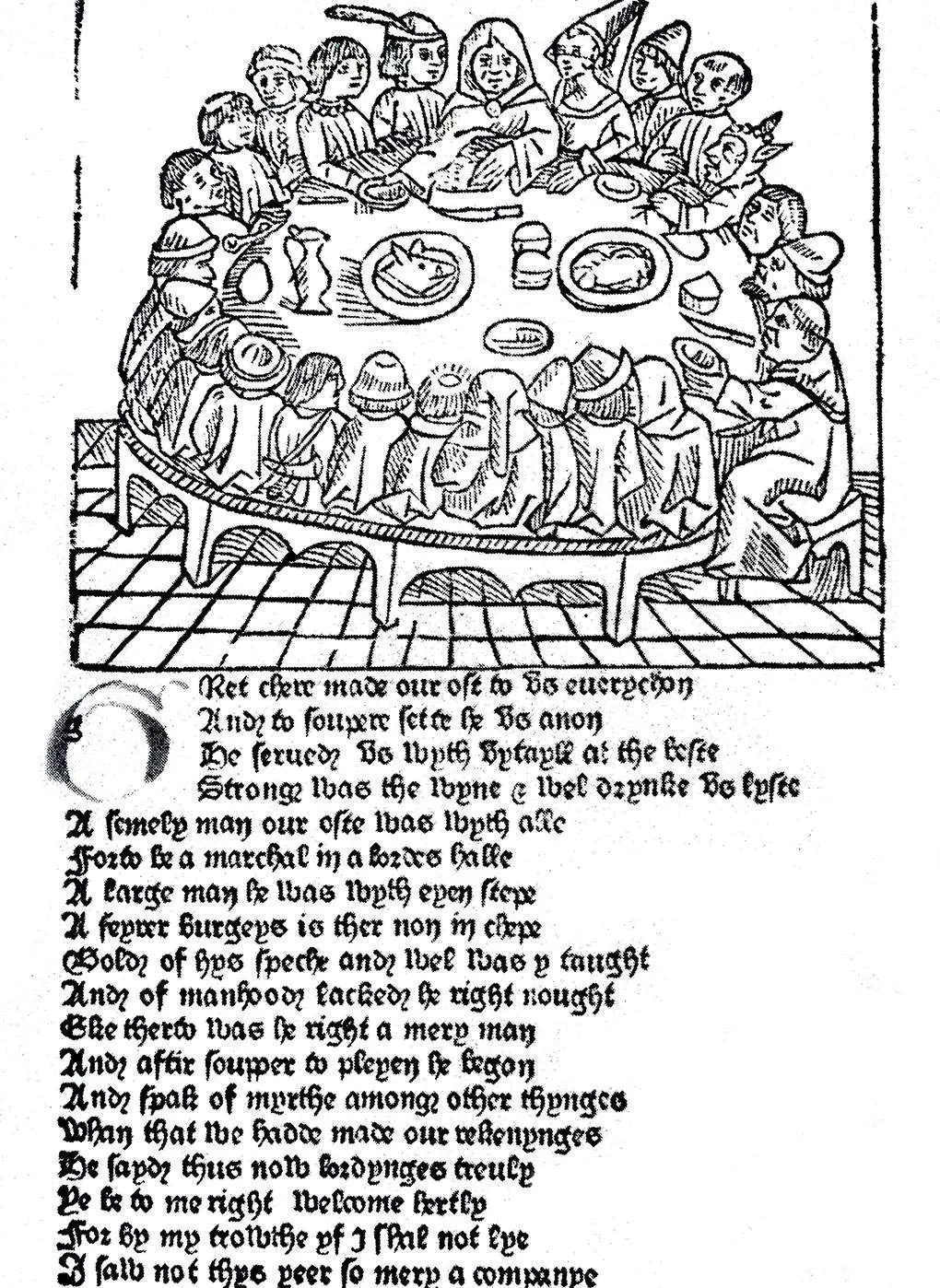

Christmas is coming; and if you think today’s festive spread is decadent, just imagine what a medieval English banquet looked like! Long before turkeys were discovered in America, people from monks to monarchs gathered round a banquet table groaning with pies, ale, spiced wine, and one very impressive centrepiece: the boar’s head.

Why Boar (and Later, Ham)?

For medieval English nobles, the boar’s head on the table wasn’t just for eating - it was a trophy. Wild boars were fierce beasts that dated back to the heroic hunts of Arthurian legend, and bringing one down was a serious achievement for any lord or knight.

But there’s more to our porky Christmas traditions than just bragging rights.

Long before Christianity softened the feast, Germanic and Norse peoples celebrated Yule - a midwinter festival marking the return of the sun after the shortest days of the year. Part of this celebration involved honouring the gods with feasting and ritual. In Norse lore, the god Freyr was associated with prosperity and good fortune, and his sacred animal was a golden-bristled boar. In some traditions, a sonargöltr — a sacrificial boar — was offered in his honor during the Yuletide feast.

As Christianity spread through Europe, many of these customs were adapted, not abolished. Feasting at midwinter was simply too beloved to lose. The boar’s head remained central to the medieval noel feast, and by the time ham became easier to cure and serve, pork had become a firmly entrenched part of Christmas fare.

So when you carve your Christmas ham this year, you’re not just slicing into delicious meat — you’re honoring centuries of festive tradition. 🐷

🐺 A Wild Hunt Through the Folklore Sky

The Wild Hunt

Now let’s add a splash of mythic winter drama: the Wild Hunt.

This wasn’t a hunting party in the usual sense, at least not for living prey. Across Germanic and Norse folklore, the Wild Hunt was a spectral cavalcade of ghostly riders thundering through the dark winter skies, led by a supernatural figure like Odin. It was thought they gathered lost souls and spirits on their swift, eerie chase.

In a world where winter meant danger and scarcity, such tales embodied the fear and awe people felt toward the season, as well as the hope that the return of light would soon chase away the spirits of cold and shadow. The Hunts’ rumbling through frost-bitten skies would have been part of the very atmosphere that made midwinter celebrations so potent and memorable.

In LADY OF LINCOLN, Nicola de la Haye goes on a boar hunt.

Her husband is away, but the castle garrison and her villagers expect a feast for Christmas.

There’s only one problem: only the lord has the king’s permission to hunt.

So Nicola finds a way around the situation: she leads the hunt herself.

The scene of the hunt in LADY OF LINCOLN, full of danger and drama, as well as the emotional aftermath, and the effect it had on her, will prove to be a turning point in Nicola’s arc. From impetuous teenager to the woman who would one day be heralded as ‘The Woman who Saved England’, this proved a turning-point in how she viewed both herself and her role.

Medieval Christmas feasts weren’t designed for the faint-hearted reveller

Re-feathered Peacock

If your Christmas dinner ever felt like too much, spare a thought for those medieval revellers. They could be feasting on peacock (with feathers re-attached for dramatic effect) alongside their boar’s head, pies might contain anything from poultry to eels, and were even sometimes shaped like castles or roaring flames, and while we sip a glass or two of mulled wine, they were tipping back huge quantities of ale or hippocras, a spiced, and very strong, medieval precursor to our favourite festive tipples.

Deck the Halls (Literally): Boughs, Holly & a House Full of Green

We have tinsel, fairy lights, and Christmas trees, but well before these, medieval people did actually deck their halls with greenery.

In the depths of winter, when fields were bare and trees stood skeletal, bringing green branches indoors was both practical and symbolic. Halls, churches, and homes were dressed with boughs of evergreen, ivy, holly, and bay, transforming draughty stone spaces into something that felt alive, warm, and festive.

Evergreens mattered because they refused to die back in winter. To medieval eyes, they represented endurance, renewal, and the promise that spring would return; ideas that sat very comfortably with both pagan midwinter beliefs and later Christian symbolism.

Holly, in particular, was thought to have protective powers. Its sharp leaves were believed to ward off evil spirits (and possibly the odd mischievous goblin), making it especially popular at Christmastide. Ivy clung stubbornly through the cold months and symbolised fidelity and eternal life, though some clergy naturallly grumbled that it was a little too pagan!

And it wasn’t just decoration. Floors were strewn with fresh rushes, herbs, and pine branches, releasing scent as they were crushed underfoot. Imagine the smell: resin, greenery, woodsmoke, roasting meat.

Of course, all this greenery tied neatly back to older Yule traditions, when people honoured nature’s cycles and coaxed the sun’s return with feasting, fire, and foliage. So when you hang a wreath or drape a garland this Christmas, you’re taking part in a tradition that stretches back over a thousand years, one that began with muddy boots, smoky fires, and armfuls of winter greenery hauled inside against the cold.

What’s a Medieval Christmas Without a Little Pagan Sparkle?

So as we string lights and wrap presents, it’s fun to remember that many cherished customs have roots that go way back; from the boar-hunting bravado of medieval nobles, to the pagan Yule feasts welcoming back the light, and even the ghostly Wild Hunt thundering through winter skies.

Whether your own celebration centres on ham, goose (which was Victorian rather than medieval) turkey (American), or a vegetarian roast, take a moment to imagine the clatter of long wooden boards, the excitement of a great hunt, and the warmth of community and family gathered round a blazing fire in the depths of winter.

Merry Christmas, and may your feast be fit for kings, gods, and honoured guests of every kind! 🎉🍖🔥